Nature, Published online: 11 June 2025; doi:10.1038/d41586-025-01778-6

A safe place.

Nature, Published online: 11 June 2025; doi:10.1038/d41586-025-01778-6

A safe place.

By Mike Fitz

If you watch any of the wildlife or animal-themed cams on explore.org, then you know that they provide an exceptional lens through which we can view the lives of individual animals. The gorilla Pinga’s leadership and maternal devotion allowed her blended family group at GRACE to heal from trauma. The California condor Inikio survived wildfire only to be prematurely evicted from her nest by another condor. The legendary brown bear Otis is a quintessential example of longevity and adaptability in bears.

During my bear cam live chats, I focus a lot on the lives of individual bears and then relate those bear’s experiences to bigger ideas. Understanding how Otis has adapted to a lower rank in the bear hierarchy, for example, allows us to better understand how old bears adapt to change and challenge.

However, there’s relatively little in the scientific literature exploring how personal connections to individual animals affect a person’s support for conservation. In fact it’s been argued that this is a myopic strategy, and most conservation efforts focus on the species level. The individual animals that we watch on explore.org each have a large and devoted following, so how might our connection to individual animals influence our support for conservation of a species? A new paper, of which I’m a coauthor, finds that individual and favorite animals can have a large, positive influence on our attitudes toward conservation efforts.

My research colleagues on this project developed an online survey of bear cam viewers that was available in summer 2019 and summer 2020. When survey participants were asked if they could identify individual bears 14% of viewers said yes, 56% responded sometimes, and 30% said no. Viewers who could identify individual bears were also asked how many individual bears they could identify. Twenty-one percent of those respondents indicated they could identify one bear, 45% could identify 2–4 bears, 20% could identify 5–7 bears, and 14% could identify more than 7 bears. When asked if they have a favorite bear 53% responded yes and 47% responded no.

So what do those results mean? Not much until we examined the answers to follow-up questions. In particular, viewers were asked to rate their agreement with the statement “the ability to learn about and/or identify individual bears influences my willingness to support conservation programs.” The question was on a scale of 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). Those who could identify individual bears agreed with that statement at significantly higher levels (4.86 ± 1.86) than those respondents who could not identify individual bears (3.31 ± 1.80). Importantly, those who said they had a favorite bear reported even higher levels of support for bear conservation (5.01 ± 1.58). These results are consistent with another study based on the same survey that found the ability to identify individual bears positively influences a person’s willingness to pay to protect individual brown bears. Furthermore, intentionally watching the bearcams when a specific bear was on screen yielded better conservation outcomes according to the survey results (that is, if you said you watched the bear cams more when Otis or 503 or another favorite bear were on camera then you were more likely to state you supported bear conservation).

A separate series of questions in the survey aimed to evaluate a person’s emotional connection to brown bears through a statistical method called conservation caring. This is a numerical measure of a person’s positive emotional connection to species or place. These questions were on a scale of 1 (strongly disagree) to 9 (strongly agree). A higher score indicated a greater emotional connection. Viewers who could identify individual bears had significantly higher conservation caring levels (7.06 ± 1.68) than viewers who could only identify individual bears sometimes (6.81 ± 1.54) and viewers who could not identify individual bears (5.85 ± 1.70). Conservation caring levels also climbed with the number of bears a person said they could identify.

If you can’t identify bears on the bear cam, then don’t worry. It’s not a competition and I’ll continue to work to give everyone the tools and stories that allow us to connect with individual bears. I also know there are many people who still care for bears greatly but don’t place as much of an emphasis on getting to know individuals. What’s more important is that we recognize the individuality of wild animals and acknowledge that they are not automatons acting merely on instinct. They think and feel and their lives are important in the conservation of entire species. Other Otis-like bears doing Otis-like things roam over wild areas of North America, and if we can secure and maintain healthy habitat for Otis then other bears will benefit.

We hope to expand on these results and publish more about the influence of individual bears on conservation. I’m also interested in exploring how interpretive events—such as the live chats and Q&As that I lead during the bear cam season—provoke people to act to conserve bears and other wildlife. After all, it’s one thing to say you support wildlife conservation, but it’s another thing to take action.

Many viewers of explore.org know that watching wildlife through webcams can be a powerful and meaningful experience. With the statistical support of this and future studies, perhaps we can inspire more parks and protected areas to utilize webcams and interpret the lives of individual animals to build greater support for wildlife conservation.

I’d like to thank the researchers who made this study possible—Jeff Skibins (who drafted this paper and did the data analysis) and Lynne Lewis and Leslie Richardson (who were instrumental in the survey design and implementation). I’d also like to thank the Katmai Conservancy for covering the expense to make the paper available to everyone through open access.

2. By Hannah Bishop – We’ve all heard of the Lord of the Rings, but the Lord of the Falls is far superior in my book!

3. Sara Curtis – May the fattest win.

4. I love you, Otis! – Claire, age 10

5. Nick Day

Fluffy and great,

salmon on my plate,

winning is my fate!

Vote for holly, don’t be late!

6. #1 grazer stan – It’s time for a new champion of fatness. Time for a bear who has put in the work day after day, night after night, dedicating herself to corpulence. It’s time for Grazer.

7. Kankana Shukla

Big butt, no neck, give me fish, give me a snack!

Vote for 402’s cub!

8. ‘Boobeary’ Derrick – Paw vote for Otis.

9. Studio Prof – Look at that, no salmon left behind.

10. Tracy Pettit – Holly – Queen of the North

I was not prepared for what I saw.

I know people say that about total solar eclipses. I interviewed a NASA scientist who explained as much. Even though I never doubted their sincerity, people who have experienced total solar eclipses say it so much—“I wasn’t prepared”—that you wonder whether the sentiment is some type of collective exaggeration, an eclipse-inspired Mandela effect.

Friends, it is not. I was not prepared.

My planning for the April 8, 2024 total solar eclipse began about three years ago after learning that my house in Maine was within the eclipse’s path of totality. Early reconnaissance work was as easy as standing outside on a sunny afternoon in early April 2021 and April 2022 and (just to be sure) April 2023 to best understand where the Sun would be in the sky. Fortunately, a spot in the driveway provided a clear view to the southwest where the eclipse would wax and wane. Might a webcam view become possible too? I thought so, and the explore.org team concurred.

So on April 8 I plugged in a webcam, pointed it toward the Sun, connected with a camera operator (thank you, CamOp Arya for driving the cam), and waited under brilliant clear skies.

I had seen eclipses before-a total lunar eclipse over Pinnacles National Park in California, a partial lunar eclipse from Katmai National Park in Alaska, and a partial solar eclipse from Stehekin in Lake Chelan National Recreation Area in Washington. The eclipsed object in each, though, whether the Sun or the Moon, remained visible throughout.

The partial solar eclipse I experienced in Stehekin prepared me to expect changes in air temperatures and daylight. During the peak of the 2017 eclipse, I felt the air cool as the sun’s intensity lessened. I heard a nighthawk, a typically crepuscular and nocturnal bird, call from the sky. Perhaps there would be a chance to observe similar phenomena as the 2024 eclipse began.

Eclipses always seem to begin slowly. For nearly an hour, I could feel or see little change except for a growing cleft in the Sun. About 20 minutes before totality, with greater than 75 percent of the Sun covered by the Moon, the remaining light shifted to a dull hue like that of a lightbulb which is not bright enough for the room. I felt the temperature decline soon after. In the waning minute before totality, daylight faded to that given by a bright full moon. The air got colder still.

The experience was fascinating, but totality during a solar eclipse is something entirely different, they say. Even 99 percent coverage of the Sun by the Moon isn’t the same, they say. I watched and wondered. Is that true?

At its thinnest crescent, the sun remained too bright to view without proper eye protection. The Sun’s final arc glowed through my eclipse glasses. Then the lights went out.

It happened so suddenly. A shadow traveling at 2,000 miles per hour swept over the land. The Sun vanished. I gasped with an almost unconscious response.

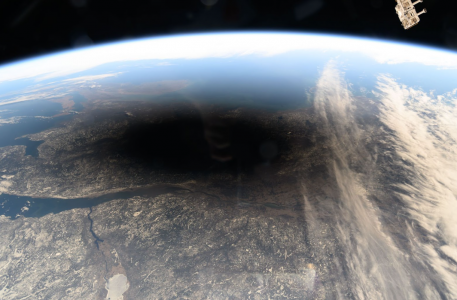

Snapshot from CamOp Orion of totality during the April 8, 2024 eclipse.

I thought I could take good photos. I couldn’t. I thought I could focus my mind to somehow slow my perception of time to prolong the experience. I couldn’t. I thought I’d try to listen for behavioral changes in wildlife. I didn’t.

Not during totality. I could only look with awe.

The Sun’s corona glowed in a halo of wispy light around the moon. Baily’s beads twinkled on the Moon’s edges. Mercury, Venus, and Jupiter appeared. The blue-black sky at zenith faded to orange on the far horizons, all horizons, like the final radiance of long past sunset.

The Moon’s shadow covers portions of Canada and the U.S. on April 8, 2024 as seen from the International Space Station. The view looks east. Maine and New Brunswick are centered under the Moon’s shadow. The Saint Lawrence Seaway is the wedge of water at left and slightly below the Moon’s shadow. The Atlantic Ocean occupies the top section of Earth. Photo courtesy of NASA.

But more than anything, it is the blackness of the Moon that I can’t get out of my head.

I’ve been in caves. I’ve led tours where I’d purposely turn out all lights to experience complete darkness, a darkness that your eyes can never adjust to. That experience removes all objects from your sight. Totality of the eclipse was different. Light remained. The Sun should have been there. It was there, as was the Moon, but the effect was so outside my normal experience that it almost defied my senses. The Sun—the brightest object I can directly perceive with my own senses–was replaced by the blackest object I’ve ever seen. The Moon became a heavenly body defined by its absence of light.

I went to bed that night thinking about it. I woke the next morning thinking about it. I’m thinking about it now, days later.

Totality ended, it seemed, as soon as it began. More than three minutes felt like 30 seconds or less. The Earth’s surface brightened the moment the Sun reappeared from behind the Moon. The look and feel of the land returned to normal within minutes.

My eclipse photos are blurry. I think the shutter speed was a little too slow or perhaps the focus was slightly off. Perhaps that is unimportant. No photo or video truly captures the experience of a total solar eclipse as you sense it. I’m not sure what to compare it to. It is like the profound difference between looking at a photo of a loved one and holding them in your arms.

Even now, I could fool myself into questioning whether I truly saw what happened. The Sun’s vanishing act was so sudden. Its most intense light was erased. If there is a moment when a person can be star-struck, this was it.

I was not prepared.

Introducing the top-voted posters of 2024!

2. Team Grazer!! by Tara Larson

3. Big Belly, Big Fun! Bead’s the cub for everyone!! by Nick Bear

4. Vote 32 Chunk for FBW, by Erica Measday

5. The Brother Bear want you to vote for Fat Bear Jr. 2024!! by Samantha Ashley

6. 128 Grazer and her cute cub. Grazer for the win. Grazer the champion of mama bears. by Nemo Laine

7. The Beady Bunch | Gorgeous. Girthy. Our Favorite Girl Gang. | reference photo by Willy Nilly, art work by Widfarend

8. Fat Bears are healthy bears! Original watercolor poster of a Bear enjoying the bounty of nature. Here’s to all of our amazing bears at Katmai! by Kristin F. Simmons

9. 901: Bodacious Beach Bod by Jo Spinner

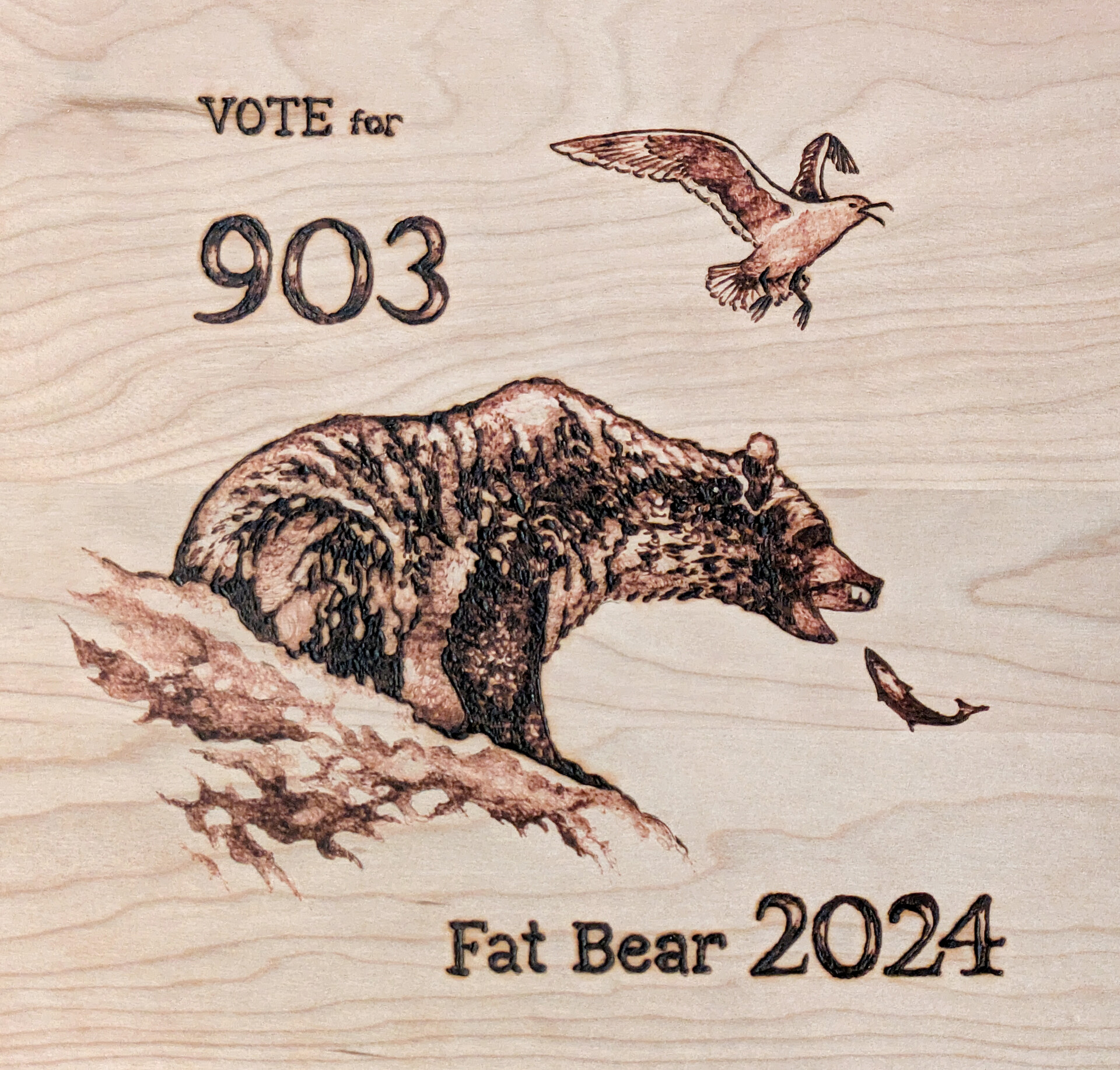

10. He’s packed on the pounds fishing while sitting on the lip. Vote for 903! by Sara (twelve22)

11. Vote for 32 Chunk !! He’s the biggest in the trunk !! by Bear Friend

12. Vote for 903! by FernW

13. Retire #480—Katmai Hall Of Fame by Stacy Jeffries

14. Vote for 806jr – the cutest cub in Katmai! Super cute, resting on his foot. Vote for the sweet 806jr! by katbears katbears

15. 901 is on the cover of FBW in the super model edition.  Vote 901. The world is her runway. She’s pretty & powerful

Vote 901. The world is her runway. She’s pretty & powerful  Photographed by Ronald S Woan, poster by Marcie Cagle

Photographed by Ronald S Woan, poster by Marcie Cagle

We’d be remiss not to include a few of the top-rated posters submitted by elementary schoolers. Here are a few from the gallery:

“Even if he can be a punk.” – poster by Wyatt C. (8yo)

Poster by Willow C. (6 yo)

Ellerhorst Elementary, Pinole, CA, poster by Ariana G.

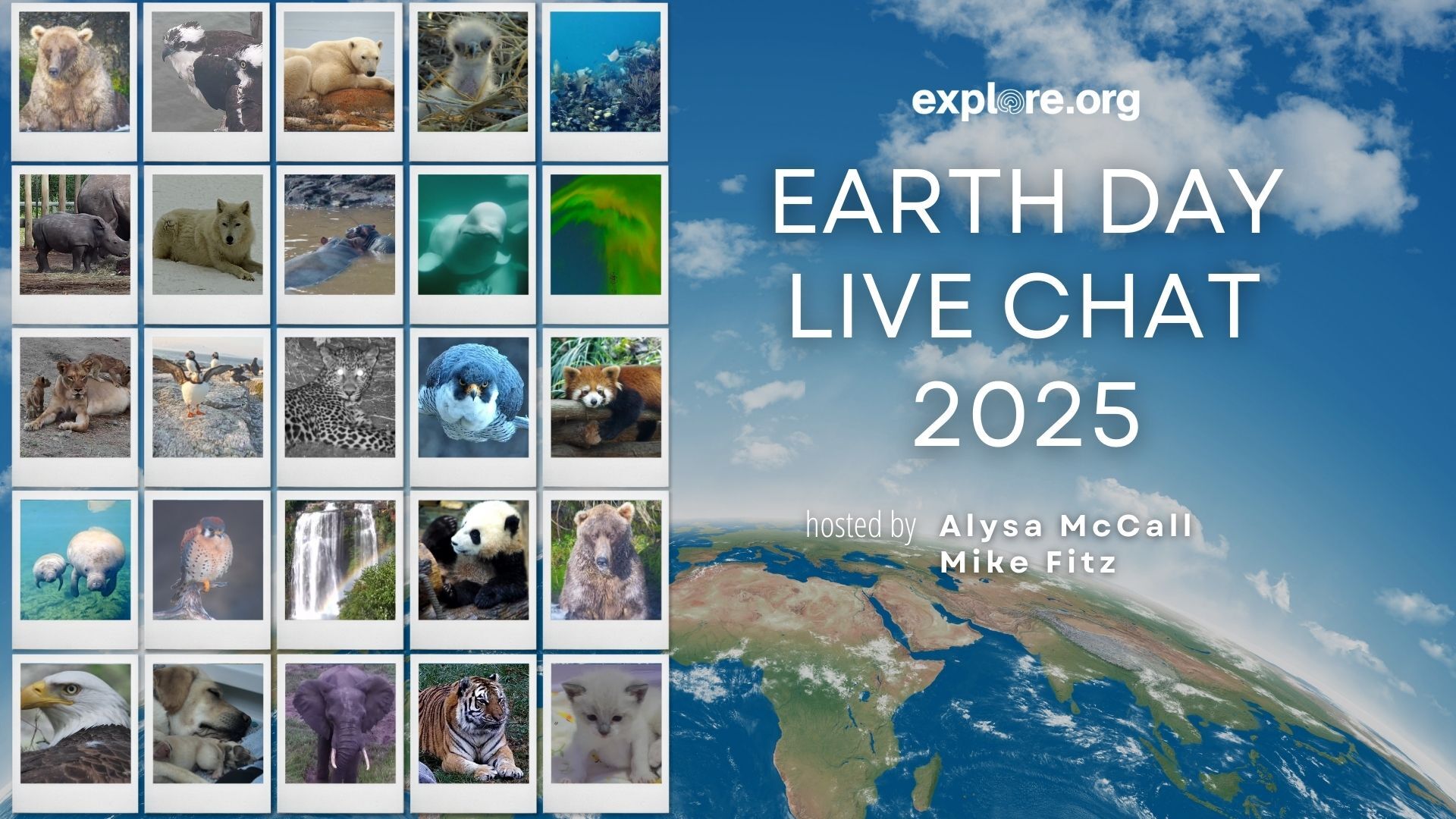

Earth Day is an annual celebration that drives environmental awareness and action. How can we support the planet and its incredible wildlife in our everyday lives?

Join us tomorrow, April 22nd at 1 p.m. ET / 10 a.m. PT for a special Earth Day livestream hosted by resident naturalist Mike Fitz and Alysa McCall of Polar Bears International. They’ll guide you through segments from our nonprofit partners:

Enjoy inspiring guest speakers, special giveaways during the broadcast, and learn simple, practical actions you can take every day to protect our planet and its inhabitants. We hope to see you there!

By Mike Fitz

Mother bears experience extraordinary energetic demands to feed their ravenous cubs. Bear families navigate a gauntlet of threats to remain safe. Cubs experience a short apprenticeship with their mothers, and they must absorb her lessons if they are to survive life as independent bears. Although sibling bears can be closely bonded as cubs and young subadults, they typically spend little or no time together as adult bears. At least, that’s what they normally do. There is no such thing, however, as an average bear or average bear family.

Bears 909 and 910 are sisters from a litter born in 2016. After separating from their mother in the spring of 2018, I expected their familial bond to weaken through their subadult years at Brooks River in Katmai National Park, Alaska. They appeared to be on that path at first. We saw them together less and less frequently as they matured into adults. Then their behavior diverged from the typical, and they gave us a chance to see a rare example of bonded mother bears and their cubs.

The subadult bears 909 (right) and 910 (left) sit on a rock in Brooks River on July 22, 2018. National Park Service photo by T. Carmack.

In the summer of 2022, each sister returned to Brooks River with a cub. 909 was caring for a yearling (second-year) cub, while 910 was accompanied by a single spring (first-year) cub. As expected, the mothers and their cubs didn’t associate closely in early summer. By mid-August, though, they became an integrated family. Bonding between mother bears has been documented previously, but it remains rare and the circumstances that influence it aren’t well understood. The relationship between the 909-910 families was something I had never seen before, so I wrote a paper about it. Their story, in brief, was published in the scientific journal Ursus. (Thanks to explore.org for covering the publication and open access fees.)

Brown bears were characterized historically as solitary and asocial. Yet, bears are intelligent, recognize each other as individuals, and can express a high level of sociability. A team of researchers proposed recently that sociability in brown bears exists along a continuum. My observations of bear behavior support this idea. Some bears at Brooks River are loners while some bears play with other bears frequently, even seeking out the company of specific bears as regular playmates. 909 and 910’s bond was deeper than infrequent play bouts, though.

At the beginning of summer 2022, they used the same places along Brooks River to fish but did not seek friendly social interaction until August. Then, after about five or six weeks of fishing on that year’s large sockeye salmon run, the families bonded. They traveled, foraged, and played together until they were last seen at the river in mid-October. The cubs would remain near each other while the mothers fished separately. The mothers would allow their nieces to take fish from their daughters and did not typically move to discourage the behavior, a tolerance akin to that shown by a mother bear when her cubs compete amongst themselves for food. The cubs would play separately from the adults, the mothers would play separately from the cubs, and the mothers would play with one or both cubs.

Why did the families bond so closely in 2022? How did kinship, or their sense of it, influence their behavior? We’d have to ask them to know for sure. Since we can’t do that, then maybe we can draw some conclusions based on their behavior and biology. 909 and 910 are siblings from the same litter and were socialized to each other from their experiences together as cubs and subadults, so they weren’t strangers. More eyes in a group increases the chance of spotting threats in advance. The cubs found consistent playmates with each other and the adults. Brown bear cub survival appears to increase with greater rates of play. Strong social bonds between mother bears may also reduce cub mortality during periods of food scarcity or social stress.

Still, 909 and 910 aren’t the first sibling bears to use Brooks River as adults. Female bears often live in home ranges that overlap with their mothers, so encounters between sister and mother bears may not be rare at all. I suspect that the large salmon run at Brooks River in 2022 was a major influence on their behavior. Notably, the families did not unite as a cohesive group until early August, several weeks after sockeye salmon arrived at the river. Food competition and stress appeared greatly reduced by early August compared to late June and July. This was also on the heels of very large salmon runs at the river during the previous few years. 909 and 910 came of age when salmon runs in Bristol Bay and at Brooks River were uncommonly large.

But this begs another question. If access to ample food allows bears to be more sociable, and if greater sociability provides possible survival advantages, then why don’t more bear families at Brooks River behave like 909, 910, and their cubs?

909 and 910 play while their cubs graze on vegetation. Bearcam snapshot taken by GreenRiver on August 30, 2022.

Bears survive by feasting when food is available and enduring famine when food is lacking. Perhaps most bears cannot overcome innate feelings of wariness and uncertainty created by competition and hunger even when food is plentiful. A high level of sociability isn’t inherent in every bear personality either. I’d rather spend time alone than hang out in a crowded place. Some bears are like that too.

Maybe 909 and 910 and their cubs experienced the ideal set of circumstances in 2022 that allowed them to bond. They didn’t suffer from any injury or illness that would have limited their ability to socialize. They weren’t overtly wary or fearful of each other. The cubs were healthy, curious, and energetic. Food was of little worry. The young mothers had a long, friendly family history. The mothers and their cubs also seemed to have personalities that, for bears, are a bit extroverted.

Finally, let’s not discount that the families had a lot of fun together. They liked each other. Not every behavior can be reduced to mere hypotheses about survival and adaptation instincts. Instinct is a powerful influence on animal behavior including humans—for example, consider how your mood and behavior change when you feel especially hungry or after you eat a satisfying meal—but non-human animals aren’t instinctual robots. They have inner lives. I have no doubt the integrated family experienced joy when their bellies were full and they could relax and play as a group. Comfort, joy, and contentment are as much of a motivator in bear lives as they are in human lives.

The relationships between these bears changed after 2022 but didn’t end. In 2023, bear 909 separated from her then 2.5-year-old cub who was soon adopted by her aunt, 910. The 910 group often fished in close proximity to 909 at Brooks Falls, yet the adults remained separate. The 910 family, including the former 909 cub, remained together through October 2024.

What will we see from them this summer? We’re entering a true golden era of wildlife observation. The behavior, sentience, and intelligence of non-human animals are more accessible and knowable thanks to webcams and the collective observations of webcam viewers. 909 and 910 and their cubs showed us that the bear world is more than struggle, competition, and hardship. It is also joy, family, and friendship.

Although I mention this in the Ursus paper, the collective observations of bearcam viewers are invaluable and I would not have been able to write my 909/910 paper without your contributions. Thank you.

Bed bugs are most likely the first human pest, new research shows.

Ever since a few enterprising bed bugs hopped off a bat and attached themselves to a Neanderthal walking out of a cave 60,000 years ago, bed bugs have enjoyed a thriving relationship with their human hosts.

Not so for the unadventurous bed bugs that stayed with the bats—their populations have continued to decline since the Last Glacial Maximum, also known as the ice age, which was about 20,000 years ago.

A team led by two Virginia Tech researchers recently compared the whole genome sequence of these two genetically distinct lineages of bed bugs.

Published in Biology Letters, their findings indicate the human-associated lineage followed a similar demographic pattern as humans and may well be the first true urban pest.

“We wanted to look at changes in effective population size, which is the number of breeding individuals that are contributing to the next generation, because that can tell you what’s been happening in their past,” says Lindsay Miles, lead author and postdoctoral fellow in the entomology department at Virginia Tech.

According to the researchers, the historical and evolutionary symbiotic relationship between humans and bed bugs will inform models that predict the spread of pests and diseases under urban population expansion.

By directly tying human global expansion to the emergence and evolution of urban pests like bed bugs, researchers may identify the traits that co-evolved in both humans and pests during urban expansion.

“Initially with both populations, we saw a general decline that is consistent with the Last Glacial Maximum; the bat-associated lineage never bounced back, and it is still decreasing in size,” says Miles, an affiliate with the Fralin Life Sciences Institute. “The really exciting part is that the human-associated lineage did recover and their effective population increased.”

Miles points to the early establishment of large human settlements that expanded into cities such as Mesopotamia about 12,000 years ago.

“That makes sense because modern humans moved out of caves about 60,000 years ago,” says Warren Booth, an associate professor of urban entomology. “There were bed bugs living in the caves with these humans, and when they moved out they took a subset of the population with them so there’s less genetic diversity in that human-associated lineage.”

As humans increased their population size and continued living in communities and cities expanded, the human-associated lineage of the bed bugs saw an exponential growth in their effective population size.

By using the whole genome data, the researchers now have a foundation for further study of this 245,000 year old lineage split. Since the two lineages have genetic differences yet not enough to have evolved into two distinct species, the researchers are interested in focusing on the evolutionary alterations of the human-associated lineage compared with the bat-associated lineage that have taken place more recently.

“What will be interesting is to look at what’s happening in the last 100 to 120 years,” says Booth. “Bed bugs were pretty common in the old world, but once DDT [dichloro-diphenyl-trichloroethane] was introduced for pest control, populations crashed. They were thought to have been essentially eradicated, but within five years they started reappearing and were resisting the pesticide.”

Booth, Miles, and graduate student Camille Block have already discovered a gene mutation that could contribute to that insecticide resistance in a previous study, and they are looking further into the genomic evolution of the bed bugs and relevance to the pest’s insecticide resistance.

Additional collaborators on this research are from Virginia Commonwealth University, University of Arkansas, University of Texas at Arlington, Harvard University and Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard, and the Czech University of Life Sciences.

Source: Virginia Tech

The post Bed bugs may be the first human pest appeared first on Futurity.

A common sleep aid restores healthier sleep patterns and protects mice from the brain damage seen in neurodegenerative disorders, such as Alzheimer’s disease, according to new research.

The drug, lemborexant, prevents the harmful buildup of an abnormal form of a protein called tau in the brain, reducing the inflammatory brain damage tau is known to cause in Alzheimer’s.

The study suggests that lemborexant and other drugs that work in the same way could help treat or prevent the damage caused by tau in multiple neurodegenerative diseases, including Alzheimer’s, progressive supranuclear palsy, corticobasal syndrome, and some frontotemporal dementias.

“We have known for a long time that sleep loss is a risk factor for Alzheimer’s disease,” says senior author David M. Holtzman, a professor of neurology at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis.

“In this new study, we have shown that lemborexant improves sleep and reduces abnormal tau, which appears to be a main driver of the neurological damage that we see in Alzheimer’s and several related disorders. We are hopeful this finding will lead to further studies of this sleep medication and the development of new therapeutics that may be more effective than current options either alone or in combination with other available treatments.

“The antibodies to amyloid that we now use to treat patients with early, mild Alzheimer’s dementia are helpful, but they don’t slow the disease down as much as we would like,” he adds.

“We need ways to reduce the abnormal tau buildup and its accompanying inflammation, and this type of sleep aid is worth looking at further. We are interested in whether going after both amyloid and tau with a combination of therapies could be more effective at slowing or stopping the progression of this disease.”

Holtzman and his team were among the first to identify the connection between poor sleep as a risk factor for Alzheimer’s disease and the buildup of proteins such as amyloid and tau. In past work studying mice genetically prone to amyloid and tau buildup characteristic of Alzheimer’s disease, they showed that sleep deprivation makes this buildup worse. Improving sleep in these mice with lemborexant appeared to be protective, the latest study showed, with less buildup of tau protein tangles and less nerve cell death associated with Alzheimer’s disease.

The protein tau accumulates in the brain in multiple neurological disorders, including Alzheimer’s, and causes inflammation and the death of brain cells. Holtzman and his team—co-led by first author Samira Parhizkar, an instructor in neurology—tested lemborexant in part because it has effects in parts of the brain known to be affected by abnormal tau accumulation. It also does not impair motor coordination, which is a concern for people with dementia taking hypnotic sleep aids.

Lemborexant is one of three sleep drugs approved by the Food and Drug Administration that inhibit the effect of orexins, small proteins that regulate sleep, by acting as orexin receptor antagonists. Lemborexant blocks both orexin receptors (type 1 and type 2). Receptors are proteins on the cell surface that bind to other molecules and regulate cell activity. These receptors are known to play important roles in sleep-wake cycles and appetite, among other physiological processes.

The pharmaceutical company Eisai provided lemborexant for these studies as part of a research collaboration with WashU Medicine focused on developing innovative treatments for Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, and other neurodegenerative diseases.

In mice genetically prone to harmful tau buildup, lemborexant reduced brain damage compared with control mice. For example, those receiving lemborexant showed 30% to 40% larger volume in the hippocampus—a part of the brain important for forming memories—compared with control mice and those receiving a different sleep drug, zolpidem, which belongs to a different class of drugs. Zolpidem increased sleep but had none of the protective effects against tau accumulation in the brain that were seen with lemborexant, suggesting that the type of sleep aid—orexin receptor antagonist—is key in producing the neuroprotective effects. The researchers also found that the beneficial effects were only seen in male mice, which they are still working to understand.

Normal tau is important in maintaining the structure and function of neurons. When healthy, it carries a small number of chemical tags called phosphate groups. But when tau picks up too many of these chemical tags, it can clump together, leading to inflammation and nerve cell death. The authors found that by blocking orexin receptors, lemborexant prevents excess tags from being added to tau, helping tau maintain its healthy roles in the brain.

Holtzman says his team is continuing to explore the reasons lemborexant treatment’s neuroprotective effects were seen only in male mice. He speculated that the sex discrepancy could be due to the observation that female mice with the same genetic predisposition to tau accumulation developed less-severe neurodegeneration compared with male mice. With less damage to begin with, potential beneficial effects of the drug could have been smaller and more difficult to detect.

The research appears in Nature Neuroscience.

Support for this work came from the National Institutes of Health (NIH), the JPB Foundation, the Alzheimer’s Association, the Rainwater Foundation, and a COBRAS Feldman Fellowship.

Holtzman is an inventor on a patent licensed by Washington University to C2N Diagnostics on the therapeutic use of anti-tau antibodies. Holtzman cofounded and is on the scientific advisory board of C2N Diagnostics.

Source: Washington University in St. Louis

The post Can a sleeping pill protect against Alzheimer’s damage? appeared first on Futurity.

A study to look at why long-lived bats do not get cancer has broken new ground about the biological defenses that resist the disease.

Reported in the journal Nature Communications, researchers found that four common species of bats have superpowers allowing them to live up to 35 years, which is equal to about 180 human years, without cancer.

Vera Gorbunova and Andrei Seluanov, members of the University of Rochester biology department and Wilmot Cancer Institute, led the work.

Cancer is a multistage process and requires many “hits” as normal cells transform into malignant cells. Thus, the longer a person or animal lives, the more likely cell mutations occur in combination with external factors (exposures to pollution and poor lifestyle habits, for instance) to promote cancer.

One surprising thing about the bat study, the researchers say, is that bats do not have a natural barrier to cancer. Their cells can transform into cancer with only two “hits”—and yet because bats possess the other robust tumor-suppressor mechanisms, described above, they survive.

Importantly, the authors say, they confirmed that increased activity of the p53 gene is a good defense against cancer by eliminating cancer or slowing its growth. Several anti-cancer drugs already target p53 activity and more are being studied.

Safely increasing the telomerase enzyme might also be a way to apply their findings to humans with cancer, Seluanov adds, but this was not part of the current study.

The National Institute on Aging supported the research.

Source: University of Rochester

The post Why don’t bats get cancer? appeared first on Futurity.